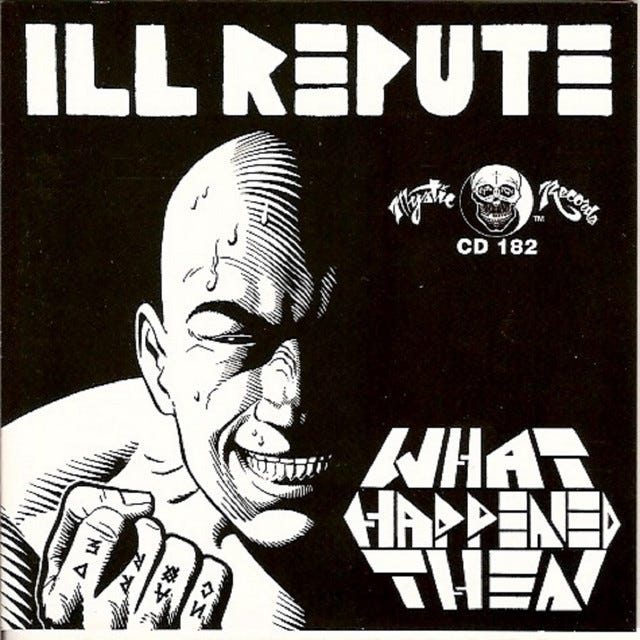

No. 105 - Ill Repute’s “Oxnard” changed my life

How a bruised up, passed around mixtape led Jacob Rhodes into the Nardcore scene and beyond

🌸 A Grace favorite

This Song Changed My Life is an independent music publication featuring weekly essays from people all around the world about the songs that mean the most to them. Created (and illustrated) by Grace Lilly.

Enjoying the series? Support here to keep the good stuff coming 😊

• 7 min read •

It was another sun-choked California summer. I was 10 or 11 or 12. It’s hard to know when every day is the same: 72 high/67 low, and a light offshore breeze.

Oxnard and Port Hueneme (referred to in classrooms across Ventura county as The Ox’s Nards and Pork My Weenie) had the perfect weather conditions and soil for agriculture, producing a bounty of strawberries, lemons, celery, artichokes, and sometimes even Christmas trees. However, my body was confusing tree and plant sperm for deadly poisons and reacted accordingly with a robust river of mucus and tears. I was a hit at barbecues and any other outdoor activity, sprawled out on a blanket, tissue stuffed up my nose, fighting a migraine.

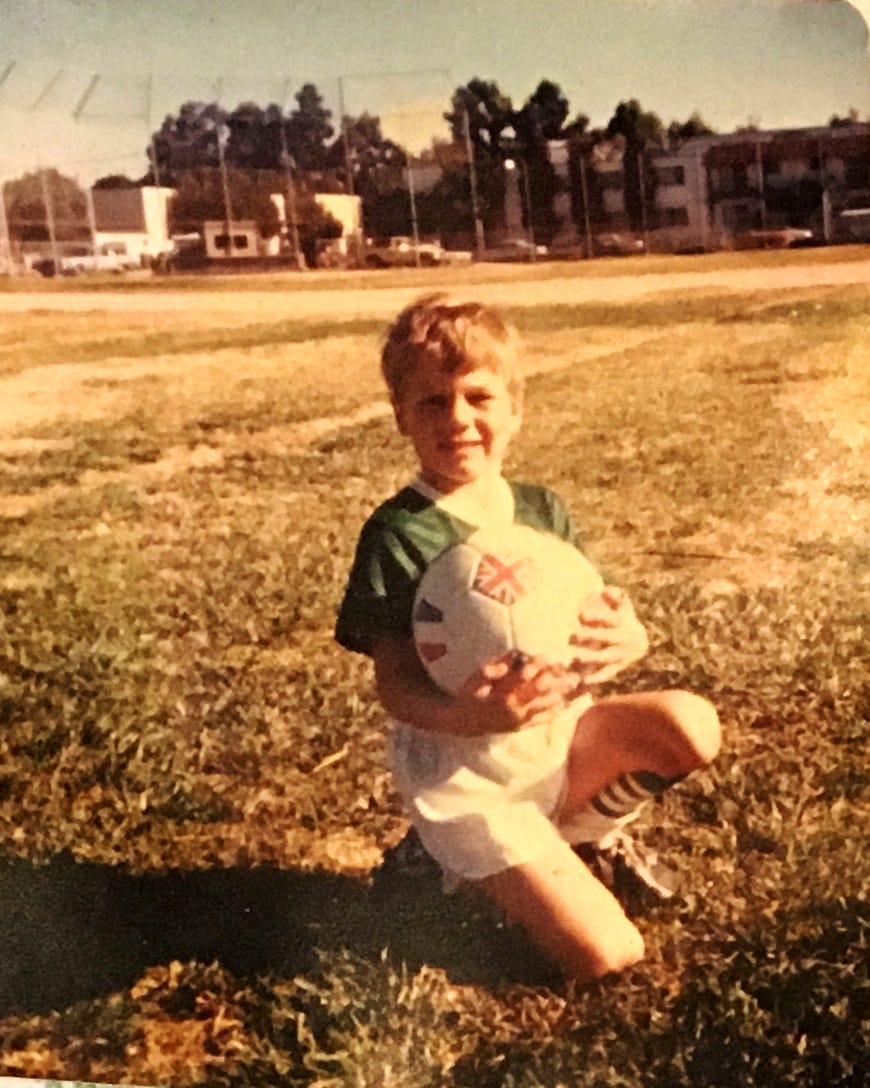

Despite that, my dad forced me to play T-ball and soccer. He thought it would “make a man out of a pussy.” Instead, I learned how to strike out, to daydream in the midfield, and that I was allergic to fucking grass.

I embraced my indoor kid life, though! I loved drawing, board games, comix, cards, TV, and of course listening to music. My parents had records left over from the 60s and 70s: the Beach Boys, the Beatles, and some random psychedelic stuff. I gravitated towards the entrancing harmonies of the Beach Boys, but their idyllic rendering of surf culture did not pair with the violent localism of our beaches.

Whenever we were on school break, my mother would drop my two brothers and me off at a local beach around 9 a.m., swim trunks, boogie boards, Zinka on our noses. “Okay, I’ll be back here around 4 to pick you up.” As she drove off in her brown station wagon, my older brother would abandon us. Dave was four years older than me, and he had friends and drugs to indulge in. Meanwhile, my little brother, Luke, and I were chum in the water to any and all of the older surfer boys with their Sun-In hair, hobo tans, and noses for prey. I can’t count the number of times we got jumped at Pork My Weenie Beach, but we didn’t get any new black eyes or bloody noses. We already had those from our father, David Senior.

My dad was a car mechanic and full-time asshole. My mom was a lunch lady and lost cause collector. Neither of them graduated high school, and they were both Christians. My Father used Jesus to justify his tyranny over us and our mom. My mother used Jesus to believe everyone could be saved. I took a more practical approach; if there was a God and he allowed what was happening to me and my brothers, He was not worth my thoughts or anger.

My home was dangerous, but my room was my refuge as long as I didn't make any loud noises or draw any attention to myself. I had a bed and a stack of six cinder blocks that acted as a low table under a large window that looked out to the brown grass and dirt of our backyard. I had recently moved out of the room I shared with my little brother and was basking in my time alone, reading soapy comix like X-Men and the Punisher, or listening to my one cassette, Bruce Springsteen Born in the USA, on my prized Panasonic RQ-2108.

My door flew open and I winced. Dave, my older brother, stood there in his teenage glory; ripped jeans, checkered low top Vans, Anacapa t-shirt, and a shit-eating grin across his face. “Wha-cha doing, dork? Why are you listening to that shit? I got something for you.” With that announcement, he whipped around and headed across the hall to his room. I sadly pushed the clunky button to shut off the sweet sounds of The Boss and made my way into Dave’s cave.

It was dark, the windows were blacked out with curtains and tinfoil. Later on Dave would sneak out these windows and impregnate our babysitter, but that’s a year or so away. Translucent scarves hung from the ceiling. The Cure, Motley Crew, and Duran Duran posters covered the walls, along with necklaces, trinkets, and charms hanging from small hooks. Dave sat at his desk, hunched over the top drawer, rifling through the bizarre things teenagers collect: lighters, sage, suede fringe, bandanas, weird oils, a rosary, cough drops, pamphlets, a folded up piece of tin foil.

I stared at a multitude of guttered candles that had morphed into a multi-colored holy mountain covering a quarter of the desktop. This wax landscape, this cordillera, paid homage to a long-fought war between my parents. “He’s going to burn the damn house down!” my dad would scream, with his neck veins bulging and his grey eyes burrowing into my mother’s. “We have to give him a chance to be responsible,” my mom would calmly reply. “He’s not responsible, he’s a dumb ass kid!” my dad would yell as he poked Dave in the chest with his thick, somehow muscled finger.

Fights like this were commonplace at our dinner table, and we all knew to keep our eyes down on the reheated cafeteria leftovers my mom had swiped from work. This particular fight went on for about a week or two before my dad agreed to let Dave have the forbidden open flame, but only if my mother “used her money” to buy a fire extinguisher for Dave’s room, and “the window had to be OPEN!” Ironically, this would make the flame more erratic, but thoughtful analysis has never been one of my Dad’s strengths.

“Here it is!” Dave had fished out a clear plastic cassette from the back of the top drawer and plunked it into my hands. I slowly flipped it over a couple times to inspect it. It was dirty and the plastic had been scratched to a matte finish. The tiny tabs in the top had been broken out to prevent anyone from recording over it. There was a paper sticker label on one side that had a symbol scratched into it with a black pen, a diamond with an X through it, kind of like an argyle.

“Thanks… what is it?”

“Local bands! Punk shit! You want to be a punk, right? Well, here you go.”

I walked back into my room, knelt by my bed, ejected The Boss from my clunky, plastic Panasonic, and inserted the filthy cassette. As I watched the take-up reel slowly pull from the supply reel I felt the sun, magnified by my naked window, hot on the back of my neck.

Over the next hour or so, I heard music that seemed to say the things I couldn’t in ways I’d never heard before. Pure energy and frantic speed combined with simple notes and honest lyrics about places I knew; not just locations on a map, “Oxnard,” but the poor-shamed places in my head. Wearing my older brother’s hand-me-down shoes, clearly two sizes too big. Holes in our thrift store shirts and pants. Hunger to escape.

And these bands spoke in the familiar language of self deprecation and irony. It’s one of the skills you pick up when you’re beaten down. “Dad only slapped you? He held me by the neck till I passed out because he couldn’t part with me. Sorry he doesn’t love you as much!” They talked about the injustice of our local lives, but also about how injustice was woven into our broader time and place.

“Oxnard,” by Ill Repute, fades in with a slow, repeating guitar, which sounds like a distant harbor foghorn warning you to steer clear. It gets closer and closer and closer, until it breaks into a speeding blur of a riff on guitar, two cracks on the snare, a speed riff, two more cracks, and we are suddenly in the fastest most frenetic music I’ve ever heard. Then the snotty adolescent vocals break in with a sweaty pit-chant scream, “OXNARD… OXNARD… NAAAAAAAAAARRRRRRRRRRRRD-COOOOOORE! I don’t care what people say…” I still don’t know what he sings after that. It’s too fast and too passionate. Nardcore is, of course, a play on hardcore punk combined with Oxnard. Another hilarious example of how to fight hierarchy, you can be proud of something and still take the piss out of it. There’s a beautiful equilibrium in that.

What changed in me in that little child’s room reflected and refracted into access to a better me, a whole me.

Soon after that day, I met lifelong friends slamming and pogoing to short-lived bands with half-wit names at garages and backyard shows. They offered participation in the Nardcore scene, and not the arrogance of hierarchy. “You see this?! It’s a C chord, and this is a G… Now go start your own band! If you don’t want to do that, make a zine about what you saw here tonight! Don’t just sit there!” I learned about socialism, feminism, Marxism, collective action, building community, fighting fascism, shutting down racism, and that capitalism can’t exist without exploitation.

What began with a bruised up, passed around mixtape led me to family, friends, education, and defining my own success. ◆

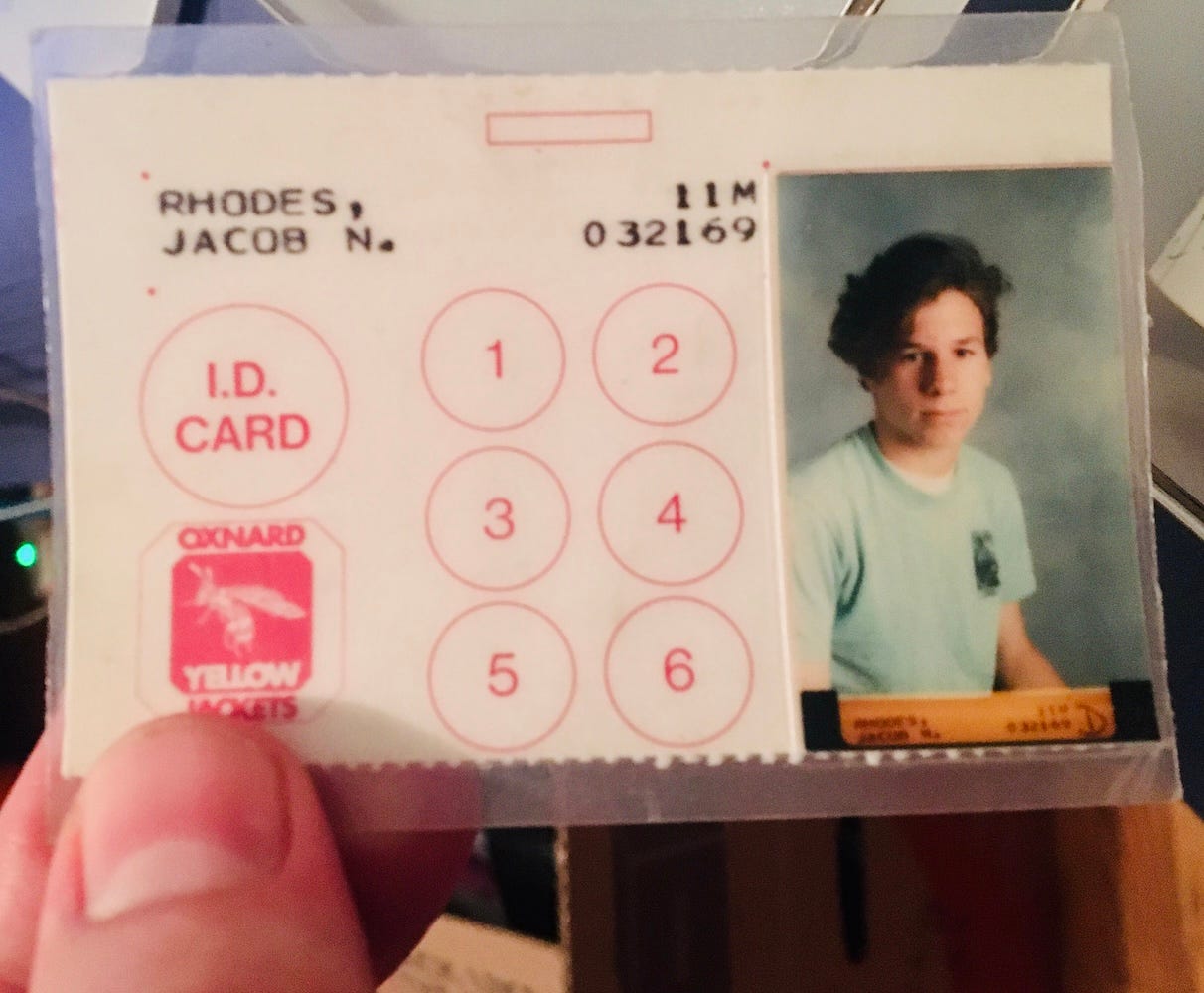

About Jacob

Jacob Rhodes is a father, artist, curator, veteran, activist and drummer. He founded Field Projects in 2011. FP is one of very few artist-run spaces in Chelsea, New York City. Through open calls, residencies, and mentoring Field Projects works to make art and the art world accessible to everyone. Jacobs holds a BFA from Otis and MFA from Yale. He played drums in a handful of Nard-Core bands: Vermicious Knids, Coathang’r Kids, Mamones, Hella Kitty, and ran the zine Aardwolf with Tom Edwards of Dick Circus fame.

Website fieldprojectsgallery.com

Instagram @jacobrhodes74

⭐ Recommended by

Tracy McKenna (No. 080)

Every TSCML writer is asked to recommend a future contributor, creating a never-ending, underlying web of interconnectivity 🕸️

This Song Changed My Life is open to submissions. For consideration, please fill out this simple form.

Categories

Friendship • Family • Coming of Age • Romance • Grief • Spirituality & Religion • Personal Development

Recommended

This is Carl - OG drummer from Ill Repute and co-writer of "Oxnard". Reading this article is truly humbling to me. When we sat down at my kitchen table 40+ years, we just had an "idea" of a song that connected with the scene. We did not imagine it would change anyone's life. Thank you Grace and Jacob!!!